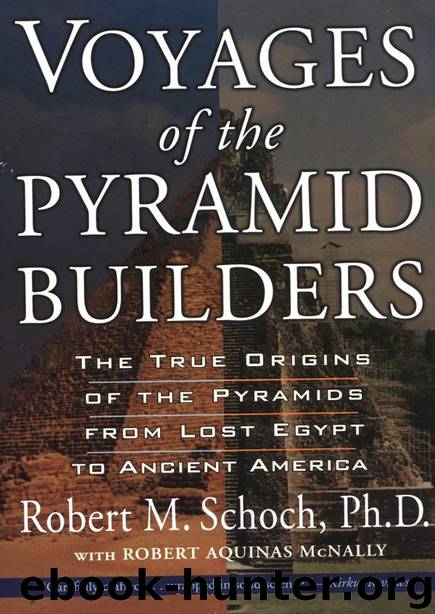

Voyages of the Pyramid Builders by Robert M. Schoch

Author:Robert M. Schoch [Schoch, Robert M.]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

Publisher: Penguin Publishing Group

Published: 2004-05-23T16:00:00+00:00

Widening the World

When Columbus set sail for Cathay (China) but instead discovered the Americas, he was breaking out from the limited vision of the world that had survived from the end of Roman times. As the Roman Empire collapsed into the Dark Ages, Europe pulled in upon itself. Knowledge of distant places vanished with the classics, and a world that had once been large and round became small and flat. In a way, Columbus was less discovering a New World than recovering a body of knowledge about navigation and sea travel that Europe had forgotten centuries and even millennia earlier.

A short inscription from the Fourth Dynasty (2575-2465 B.C.) about the import of cedar logs by ship, most likely from Lebanon, shows that Egypt’s Old Kingdom made use of maritime trade. Since the Egyptians of that time were less than sterling seafarers, it is likely that the ships plying the lumber route hailed from Lebanon, probably the Phoenician port of Byblos. In about 1460 B.C. the Egyptian queen Hatshepsut dispatched vessels to the unknown port of Punt to fetch rare trees and woods, monkeys and apes, gold, and the incense myrrh. Scholars place Punt somewhere at the southern end of the Red Sea in modern Eritrea or Somalia, meaning a total round-trip journey of some 3,000 miles.

At some later date, the Egyptians may have made it as far as Australia—albeit almost certainly by accident. An inscription in Hunter Valley, about 65 miles north of Sydney, commonly known as the Gosford Glyphs, is thought by some writers to represent Egyptian hieroglyphics dating to anywhere from the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 B.C.) to Ptolemaic times (323-30 B.C.). If the inscription is authentic—and there is no proof as yet that it is—it tells of an Egyptian crew that was blown far off course, landed in a strange place thousands of miles from home, and wanted very badly to return.

To the west, the Egyptians apparently went no farther than Crete, perhaps because they didn’t have to. The Minoans, who flourished in the first half of the second millennium B.C., were accomplished maritime traders whose great cities, like Knossos on Crete and Akrotiri on Thera, displayed both great wealth and a surprising sense of security. The Minoans had no apparent fear of attack. Their archaeological sites yield few weapons, their cities lacked walls, and only one of their exquisite frescoes shows a battle scene—and that one is at sea. From 2000 B.C. until their subjugation by the Mycenaean Greeks approximately 600 years later, the Minoans traded actively with Cyprus, Greece, Egypt, and Syria. They also ventured into the western Mediterranean, as indicated by ship graffiti on a temple on Malta. According to legend, King Minos, who gave the Minoans his name, led an expedition to Sicily.

The Mycenaeans traded their jewelry, weapons, and possibly wine for the amber, tin, copper, and gold of northwestern Europe. The shape of a twelfth-century B.C. Mycenaean dagger carved into one of the rocks of the later stages of Stonehenge underscores the connection between the Mediterranean and England.

Download

Voyages of the Pyramid Builders by Robert M. Schoch.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23062)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5070)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4761)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4672)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4189)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3539)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3181)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2659)

The History of Jihad: From Muhammad to ISIS by Spencer Robert(2611)

No Room for Small Dreams by Shimon Peres(2355)

The Turkish Psychedelic Explosion by Daniel Spicer(2344)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(2340)

Gideon's Spies: The Secret History of the Mossad by Gordon Thomas(2328)

Arabs by Eugene Rogan(2289)

The First Muslim The Story of Muhammad by Lesley Hazleton(2256)

Come, Tell Me How You Live by Mallowan Agatha Christie(2241)

Bus on Jaffa Road by Mike Kelly(2138)

Kabul 1841-42: Battle Story by Edmund Yorke(2013)

1453 by Roger Crowley(2013)